Killers and victims

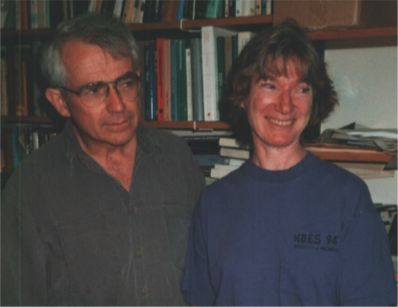

Martin Daly and Margo Wilson

Martin Daly and Margo Wilson worked for much of their careers with

monkeys and mice, but nowadays they are mainly known for their research on

homicide. Among their many publications is Homicide (1988). The following

interview took place at the 1996 conference of the 'Human Behavior and

Evolution Society' in Evanston, Illinois, USA.

Why did you investigate murder?

Margo Wilson:

We had different ideas and hypotheses about interpersonal conflicts,

for instance marital conflict, sexual conflict, parent-offspring conflict, and

conflicts in a competitive setting too. We were trained in animal-behavior, and

we have maybe an innate distrust of what people say.

About sexual conflict, a long time ago I thought, well, maybe we can go

to shelters of battered women and talk to the women, but then we thought: No,

who is using these facilities? It is a very biased sample. If you know before

what way the bias is going, then you can deal with it, but we did not know.

One day we were moving from California to McMasters in Canada and came

through Detroit, and we thought, my God, the murder-capital of America, why

don't we use homicide? All cases get reported and investigated, so there is no

bias in the sample.

We contacted the chief of police in Detroit; he had a Ph.D. in sociology

and was very interested in research, and he said "Yes, come!" So we

went there, the first time in our life we were in a police-station, looked at

the information he had, and realized we could do a ton of things.

In your book you give statistical data on victim-killer relationships, for instance how often men kill other men, how often parents kill offspring and the other way around, how often males kill females, females males, etc. You write in your book that you were amazed to discover that no one had ever compared an observed distribution in victim-killer relationships to what was expected in the light of any sort of theory of interpersonal conflict. Are you saying that, except for your own theory, there actually is no theory of homicide?

Martin Daly:

Homicide research has been dominated by sociologists who are interested

in what they call 'macro-social determinants of variation in gross homicide

rates'. Another group of homicide researchers has been psychiatrists interested

in 'abnormal perpetrators'. But there has been very little attention to the

demography and epidemiology of homicide, that is, to questions like:

"Within the married population, what are predictors of who is likely to

kill whom?" I think it fair to say there has been essentially nothing,

except for statements like: "People in bad circumstances might be more

likely to kill their children".

You show with a long list of data from all kinds of places and times, that males kill other males at least fifty times more often than females kill other females. I once heard the explanation that as one male can inseminate many females, it is good for the survival of the species that males do all the dangerous, risk-taking jobs. What is your opinion about this explanation?

Martin Daly:

Survival-of-the-species, or good-for-the-species kinds of arguments are

unpopular among evolutionists, for the reason that it doesn't make sense that

natural selection should have favoured attributes which serve the interests of

species. Natural selection is overwhelmingly a matter of differential

reproductive success of individuals within a species. Doing the right thing for

your species is likely to lose out in competition with doing the right thing

for the proliferation of related individuals likely to carry the heritable

substrates of the same traits, whatever they are. Nepotistic attributes are

likely to spread in a population to be evolutionary stable, whereas those

things that are good for the species nevertheless cannot evolve.

So why are males more violent than females?

Margo Wilson:

Females don't have the same potential for reproductive success as males

do. A woman can only have a child once every few years until menopause, so, in

contrast to males, there is a finite possibility. Compared to a man there is no

payoff for being dangerously competitive.

It's a zero-sum game among males, and competition among males for access

to females, a form of sexual selection, has designed the male mind to be both

more confrontational and dangerously risk taking. Some men will have a lot of

access to women, others will have very little, and this may have to do with

attributes like how many resources they have, how powerful they are, and how good

they are in keeping other men away from their females.

Martin Daly:

The general notion that seems to apply across the animal kingdom is that high variance in outcomes and high rewards for being a winner, and high probability for being a total loser, in combination select for higher risk competition tactics. Perhaps it is worth saying in trying to explain this argument, that the woman who stays out of trouble and keeps her nose clean, is likely to have successful pregnancies; a male who merely keeps out of trouble is likely to die celibate, and dying celibate is no better than dying young trying harder from a natural selection perspective.

You show that co-offenders are six times more likely to be blood-relatives than victim-killers. Why is this something you would expect?

Martin Daly:

The prevailing criminological model in sofar as there was an explicit

one for who is likely to kill whom, is an opportunity model. Obviously you are

not going to get into conflict with people you don't interact with. The more

often and intensely you interact with them, the more opportunity for conflict

to arise. We wanted to say, yes, obviously there is a lot of truth to that, but

over and above that, given a certain level of opportunity or interaction, there

is differential likelihood of conflictual versus cooperative motives to arise

in relation to relatedness. Your kin are, to use the jargon of evolutionary

theory, the vehicles of your fitness; -your offspring the most obviously, but

collateral kin as well. So we thought it would be interesting to investigate

the victim-killer versus co-killer relationship. We don't know how much people

interact with relatives and non-relatives. But whatever that distribution is,

if the opportunity to form cooperative alliances in dangerous endeavours is

distributed according to interaction frequency, the opportunity to come into

conflict is similarly distributed. By a pure opportunity-model these two

things ought to be similar. But it doesn't work like that. People tend to collaborate

with their relatives and they tend to do damage to nonrelatives.

Step-children seem to be a special case. You show that step-children are a hundred times more often fatally abused than genetic children.

Margo Wilson:

Parental investment is a valuable resource that you could allocate to

different activities. It takes a lot of time and effort and self-sacrifice, so

you would expect that selection would have shaped both mothers and fathers in a

biparental species to allocate that investment to own offspring, because

otherwise you would be contributing to rivals. Children that are not yours, or

not your kin, you would expect the psychology to be such that you would discriminate

against them, and you would be more reluctant to invest in them. The emotional

experience would be that perhaps you love them less.

A year or so ago we published a paper on qualitative characteristics

that are different for when genetic parents kill their children versus

stepparents. It looks like the emotional context where the genetic parent kills

is in sort of sorrow, not in anger, while in stepparents it is in anger. The

stepparent is more likely to assault to death, beat it to death, while in the

genetic parent it is smothering or maybe it is shooting.

Also, the genetic parent is more likely to kill self in the same

episode, and the stepparent doesn't. So there are cues from the context of the

homicide that sort of betray us that there is a very different background that

is causal to this outcome.

But killing is a rare outcome, the tip of the iceberg.

Martin Daly:

You may have heard of the sexually selected infanticide phenomenon, the

phenomenon of a new male who takes over a troop of langurs or pride of lions

and more or less routinely kills off his predecessor's offspring. This

terminates, from his perspective, the female's wasted investment in his

predecessor's young and gets her on to breeding with him sooner. At a very

distal level there is an analogy, but we do like to stress in this context that

it seems pretty clear that there is not anything like a sexually selected

infanticide adaptation in the human animal, certainly not like in a lion or a

langur. Humans don't routinely do that anywhere. And for everyone who kills or

dramatically mistreats a stepchild, there are many who make some degree of

parental-like investment to the stepchild, and actually do it a favour.

Couldn't the behaviour of the stepchild be responsible for the aggression of the stepparent?

Margo Wilson:

That is something you would expect with older children, who are talking,

walking and are annoying to the parent. But I know of nothing that would give

you the expectation that a small infant treats a stepparent differently than a

genetic parent. And we found that the biggest risk is for the youngest, under

three years.

In Holland when someone treats you badly, they sometimes call this a 'stiefmoederlijke behandeling'. That is, you are treated as badly as a stepmother supposedly treats you. Why a stepmother and not a stepfather?

Martin Daly:

We looked at a sort of cross-cultural compendium of folklore, and a

'stiefmoederlijke behandeling' is apparently worldwide. These stories are

everywhere, and stepmother-stories are apparently much more prevalent than

stepfather ones. When you think about stories, folktales and those sort of

things, you have to ask: Why do these things exist? They have to fulfil the

social purposes of the people who tell them, and they have to be interesting

to the people who hear them. My take on cruel stepmother stories is that the

people who tell them are genetic mothers; they tell children how awful

stepmothers are, and the secondary message is: The worst thing that could

possibly happen to you is for me to disappear and your father replace me.

But why is the father not telling the same thing about stepfathers?

Martin Daly:

He probably doesn't tell anything to the kids, but if he does, he is

more likely to tell cruel stepfather stories. But whether stepmothers are more

risky to kids, we don't have actual information about that. Our best estimate

is that the risk is similar.

Nowadays very young children almost never live with stepmothers. The

'Snowwhite,' 'Cinderella' and cruel-stepmother stories probably originate

from the times when stepmotherhood was not all that rare, because of high

mortality of young mothers.

Why do husbands kill their wives, and why do wives kill their husbands?

Margo Wilson:

One situation that is associated with men using violence against their

wives is that of sexual jealousy, that is, the man thinks or fears his woman is

having an affair with another man. Another situation that may turn dangerous

for the woman is when he thinks she intends to terminate the relationship. In

both situations the man is at risk of losing control of his wife's reproductive

capacity and is hence losing ground in the reproductive competition between

men.

Men use violence and threats against their wives in an attempt to regain

this control, and an extreme outcome is the man who kills his wife.

Martin Daly:

The motivations for women who kill their men appear to be completely

different. The dominant theme here is a struggle to resist coercion. Most

commonly, women kill in self-defence against husbands who are abusive against

them, their children, or both. Regardless of which spouse ends up dead, the

husband is usually the instigator of violence.

When people think of biologists, they often imagine someone putting rings on the legs of birds, or looking through a microscope. Your proposal that the social sciences should consider themselves branches of biology, probably sounds surprising to these people.

Margo Wilson:

We mean by the word biology what the dictionary says, which is the study

of life. And since people in the social sciences say they are also studying

'life', then, of course, we are all in the same business. We have different

specialisations which have to do with what aspects of life, or the kinds of

perspectives we bring to bear, or the kinds of explanations we are interested

in. People, including biologists, often misuse the word biology. When they

should be talking about physiology or endocrinology or genetics, they should

say that. Biologists sometimes say about a cultural phenomenon: "This is

not my subject, because I am a biologist." But cultural phenomena are by

definition biological phenomena.