Then you are in bad luck

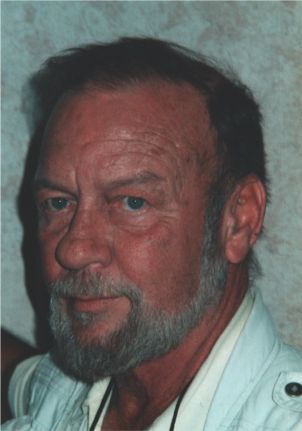

Napoleon Chagnon

Generations of social science students were electrified by reading

Napoleon Chagnon's Yanomamö, the Fierce People (1968), a monograph on a

South-American Indian tribal people (click here

for pictures). The film (now interactive CD-ROM) The

Ax Fight, which shows an escalating conflict within a village, is an

anthropological classic. Since the first time he went there in 1964, Chagnon

has revisited the Yanomamö almost every year. The following interview took

place in Tucson, June 1997.

You write that anthropologists often discover that the people they are living with have a lower opinion of you than they have of them.

When I went down there I had a Noble Savage view of what tribesmen were

like. I had gone there to learn about their way of life, and I expected them to

be fascinated and interested and even grateful for my going there. I was

assuming that they were interested in having other people know about them. They

were not; they didn't know there were other people!

Did the Yanomamö give you a hard time?

I have spend a lot of time with the Yanomamö, in total now close to six

years. But initially when I went to live with them for the first time, I was

completely unprepared emotionally to live in a society as primitive and as

savage as the Yanomamö. They were pushy, they regarded me as sub-human or

inhuman, they treated me very badly.

In their culture they expect people to be generous. They emphasize how

important it is for you to be generous, and give your things to them, by

making their needs seem to be more urgent than they really are. The more I was

reluctant to give things away at sometimes outrageous demands that they made,

the more urgent they tried to represent their needs. If I did not give my

things, disasters would befall them, and possibly me. It was a way of coercing

me.

Was there a happier side?

The happier side, the more pleasant and the truly enjoyable side, was

the consequence of a long period of getting to know them, and their getting to

know me. A qualitative change in our relationship occurred when I went home

the first time and then returned. During that period of time they apparently

discussed me, discussed the things that I did, and basically concluded that I

wasn't such a bad guy after all. More and more of them began to regard me as

less of a foreigner or a sub-human person and I became more and more like a

real person to them, part of their society. Eventually they began telling me,

almost as though it were an admission on their part: "You are almost a

human being, you are almost a Yanomamö". Yanomamö means 'human'.

You write about a sense of urgency to study them.

It became very clear to me after years of university-training, reading

lots and lots of monographs about tribal peoples, that I had stumbled accidentally

upon an extraordinarily unusual and short-lived opportunity. Because very few

people were as remote and isolated as the Yanomamö were. And I realised from

knowing how quickly acculturation can happen, that if I did not decide for an

intense and long term commitment to learning about these people while they

were still the way they were, that valuable opportunities to learn many

important things about them would disappear.

Is it a primitive people?

Yes, but keep in mind that primitive is a technical word in anthropology

to refer to those societies that are organised basically around kinship

institutions. In other words, primitive societies are those whose entire social

organisation is built on, and a function of kinship institutions, like

lineages, clans, marriage alliance systems, and they do not have other kinds of

social systems like the state, police, courts.

Is each village autonomous?

Each village is a politically independent unit, it is almost like a

nation all by itself.

Please describe some aspects of their culture.

The technological component and other aspects of their culture is more

similar to hunting and gathering peoples than it is to agricultural peoples.

They are agriculturists, but it is almost as if they want to keep one foot in

the hunting and gathering stage, and the other foot in agriculture. So their

entire cultural paraphernalia is very limited. They have hammocks, baskets, a

few very crude poorly fired claypots which have now disappeared in the last

twenty years, bows and arrows, and not much else. A whole village of Yanomamö

can pack up in five minutes and go off into the forest, and carry everything

they own. So their technology and the number of material items they have is

very, very limited, almost as though they are nomadic hunters and gatherers,

but they are not.

Linguistically, and this is not unusual, their ways of evaluating and

enumerating things in the external world are more based on the specific

properties of things; like the arrow that has a slight bend in it, or the arrow

that has a scorch-mark on it. If you show a Yanomamö ten arrows, and you decide

to steal one from him, he will notice immediately that it has gone because he

recognises the arrow by its individual properties. But they have no way of

saying: "I have ten arrows". They will say: "More that two

arrows". In their language the words they have for enumerating objects

are "one", "two", and then "bruka", and

bruka can mean anything from three to three-million.

As for their clothing, from our point of view they are naked. In an

uncontacted Yanomamö-village the men and women wear basically a few cotton

strings around their waists and their forearms. The men tie their penis to a

cotton string around their waist. But if their penis becomes untied, they are

extraordinarily embarrassed.

If there is no state, no law, no police, then how are the bad guys

controlled?

What makes a guy bad is what his enemies in other villages think of him.

In his own village he would not be considered a bad guy, he would be considered

a hero. Now within the village they have certain rules about what is

appropriate behavior with your kin and your neighbors. You should not steal the

food of members of your village, but it is perfectly alright to steal food from

other villages. You should not kill people in your own village, but it is

appropriate to kill people in other villages, if they are your enemies. We have

the same rules.

So 'bad' is a relative term, but there are nevertheless people whose

range of behavior within the village can get excessive. I know a particular

headman that I wrote quite a bit about, who had become so brutal and so homicidal

that even people in his own village did not like him. A bad guy can become a

tyrant, and very few people in that village were willing to challenge the

tyrant. There are no social mechanisms to deal with somebody in the village who

has gotten out of hand. In our culture we can call the police and have him

arrested. In their culture, if they want to challenge that guy, they have to do

it as an individual. And if this guy is a brute and quick to pick up his club

or his weapons, you better be equally good.

They live in communal dwellings?

Even though to us it looks like a communal dwelling, each part of it is

constructed by an individual family, and they just link them together. They

cooperate when they build it to make it circular and enclosed for defence

purposes.

Defence against whom?

Defence against enemies, other Yanomamö. They try to make a completely

enclosed, circular village, to us it looks like it is a communal village, but

each section of that village is a private household. Even though it is wide

open and you cannot tell. They all live together under one roof, they can see,

smell and hear each other, and life is extremely public.

Are extramarital affairs possible?

They are possible, and many young guys attempt to have them, in fact

many old guys attempt to have them. Sometimes the women are quite willing and

cooperative in this. They may decide that they like the flirtatious approaches

of a young guy, and they will quickly and discretely say: "Meet me in the

garden by my bareama kakö banana-plant". And they may have a

clandestine affair, but they will keep it secret of course. Men are always

looking where their women are, and if their wife is away for more than a few

minutes without the husband knowing where she is, he begins to get suspicious.

And even the suspicion of infidelity will cause brutal fights. So the men are

constantly tracking where their women are, what they are doing, and if the men

happen to be on a hunt for example, they have informers in the village who

will tell them: "Your wife was out with some other guy", and that is

sufficient to cause a fight.

The informer may be lying....

Not if the man picks his informer intelligently. The informer is usually

a close relative, like a brother of the man.

It is basically a male-dominated society?

Well, a lot of societies are male-dominated, and the Yanomamö are not

unusual in that regard.

If you grow up either as a boy or a girl in Yanomamö-society, will you get a different view on life?

Little girls learn quickly that they have less freedom than little boys.

They become economically useful assets to the household compared to little

boys, they have to start collecting water when they are very young, help mum

carrying food from the garden, baby-sit, and they tend to become adults much

younger in their life than little boys do. Boys can extend their childhood as

little boys can in Holland or Germany or the United States until they are

thirty-five of forty years old, before they start doing anything serious and

responsible.

Young men are always a constant problem in Yanomamö villages. Once they

are post-adolescent, they begin to have sexual interests, they are called huya,

young men. Huyas are a big pain in the ass. Huyas in all cultures are a big

pain in the ass. Gangs; juvenile delinquents.

But I guess they can be used by someone?

Well, they are useful because they can shoot bows and arrows and they

get impressed into military service just as we do with our huyas in Western

industrial civilisations.

Are the Yanomamö patrilocal or matrilocal?

Adult brothers try to remain together for cooperation and defence, you

can trust your kinsmen more than you can trust strangers. Brothers tend to be

very cooperative and quick to defend each other. And without police or state or

laws and courts, your only source of defence is your kinsmen. And the more

closely you are related to your relatives, the greater is the probability that

they will defend you, whether you are right or wrong. But they expect you to

defend them, and kinsmen in general to defend each other, whether they are

right or wrong.

What if you don't have any kinsmen?

Then you are in bad luck. Now, regarding patrilocality and where people

live after marriage, if you look at primates like chimpanzees, they are doing

basically the same thing as humans are doing. One sex migrates into the other

group, and that same sex of the other group migrates back into the original

group. What humans have done is say: Let's get the two groups together and live

in the same community. So villages tend to be constructed by two or more

lineages or clans, groups of people who are related through the male line, just

like we inherit names in Western civilisation. All of the people who have your

last name would be a member of a patri-lineage. So you end up with villages

that tend to have a dual organisation: two families that exchange women back

and forth.

But women sometimes do live in villages where they were not born.

Lets say two villages that have been enemies decide to become allies,

because both realise that they have many other enemies out there, and the best

thing for them to do, to deal with their other enemies, is to become friends.

One way to make friends with people in other villages who are potentially enemies,

is to give a woman to them in marriage. But you don't do this without great

concern for the safety of the girl. She does not want to live there; her relatives

compel her, they have authority over whom she marries. Marriage is something

too politically important to groups like the Yanomamö and presumably

throughout our history, to allow the whims of young people to have charge of it.

So for political reasons two villages who want to become friends, may

decide that the best way to do that is to start exchanging women. We'll give

you one of our young women, for one of yours. It is usually the prominent men

in the village that do this. And if the first village gives a girl to the other

one, they expect the man who is going to marry her, to come and live in their

village for several years. So the young man will do bride-service in the

village where his wife lives, and her family can get to know him, they sort of

sniff him over. After a two or three year period, during which he has to do a

lot of tasks and favours and hunt for the father in law, he'll be allowed to

bring his wife back to his village. But the women never like that arrangement,

because once she is in a different village, she doesn't have her brothers to

protect her. And since she is a stranger in the other village, she is more

likely to be approached by a lot of other men for sexual activities. This

means that her husband, who will resent this, will not only get into a lot of

clubfights with these other men in his own village, but he will punish her

too. So the life of a woman who has to live in a different village where she

doesn't have brothers, can be very, very tragic in many cases.

You write that most fights result from disputes over women. Why are

women so scarce?

For several reasons. The primary reason is that successful men often

have two, three, up to five or six women. And if a guy has five wives, about

five guys are going to have no wife. So polygyny creates a shortage of women.

From the point of view of the male, women are a scarce commodity. And if men

want to be reproductively successful they have to do a lot of social maneuvering

and manipulation in order to find a wife of their own. A man's career may start

out with not having a wife, but maybe his brother will share his wife with him.

So early in a man's career, he might be polyandrous, two or three brothers

sharing one woman, and then as he becomes more prominent, he might acquire his

own wife.

Women are also abducted in raids, which reminded me of what chimpanzees are doing.

The recent work among chimpanzees indicates very clearly that once the

chimps were no longer provisioned to the level they were before, and returned

to a more natural kind if existence, researches began to make realisations and

discoveries that they had never made before. Chimpanzees send out patrols to

their borders, they are constantly guarding borders and looking for opportunities

to invade and kill members of another group, snatch female chimps, and bring

them back to their own group.

But Yanomamö don't get their women raiding. Even though occasionally

women are captured in raids, that is not the purpose or the function of a raid.

The raid is usually to get revenge for a previous death. If a woman happens to

be away from the village, and the raiders can safely take her back with them

without her screaming and giving away their location, they will do it. But

abduction is not necessarily or very frequently done on raids. Most of the

abductions are done right at home. A group of Yanomamö from another village

will come and visit. If the visitors have women with them and their neighbours

are mercenary, they may just take the women away from the men and send the men

packing. That's how most abductions are taking place.

Why did the visiting group pay a visit in the first place?

Every Yanomamö village, -the leaders in them-, knows that eventually it

is going to be harassed by a coalition of other Yanomamö villages. So each

village has allies, but allies tend to exploit each other. Say we have two

villages of two-hundred Yanomamö, and they are allied. Since they are the same

size, they can inflict equal harm on each other. But what happens if one of

these villages splits in two and part of them goes away? Now you have a village

of two hundred Yanomamö that has an alliance with a village of one hundred

Yanomamö. Then the one with two hundred has an advantage over the one with one

hundred. So, even though for years they may have been visiting in a friendly

way, the guys who have two hundred people in their village will decide, maybe,

one day, when this friendly visit happens: "Hell, we outnumber them, lets

just take their women". And then this last village will do everything they

can to recover their women, and that often will lead to war. So balance of

power is very important; Western civilisations have always been very alert to

changes in balance of power, and it is the same for the Yanomamö.

If the size of a village is so important, why do villages split?

Because there is a limit as to how big human communities can get if they

are organised only by kinship. They fission into smaller villages because you

cannot control the violence and squabbling and fighting that begins to take

place once a village gets large.

Judging from your descriptions, the Yanomamö are a very violent people.

One of the reasons that I felt it was urgent to study the Yanomamö was

that I was one of the few anthropologists who had an opportunity to study a

tribal society while warfare was still going on, and not being interdicted by

the political state. Even though anthropology has a lot of literature about

warfare and violence, the number of anthropologists who studied tribesmen

while still at war you can count on the fingers of one hand.

Now you just told me that the Yanomamö are a really violent people. My

reaction to that is: The Yanomamö stand out because they are one of the few

societies that have been studied by an anthropologist at a time that they had

warfare. Had anthropologists been around before Columbus in North America, I

am sure that levels of violence among native Americans would be strictly

comparable to those found among the Yanomamö. And the probability is very high

that in our own tribal background violence was very common as well.

Anthropologists often call peoples like the Yanomamö 'egalitarian' societies.

One of the common misunderstandings in scientific anthropology is that

the status of people in society is basically determined by the access that

they have to material possessions. We tend to think of status being intimately

associated with the control and ownership of material things. Thus in anthropology,

groups like the Yanomamö or the !Kung bushmen are called 'egalitarian

societies', everybody is equal, because everybody has the same number of

resources. I think that is an absolutely silly and prejudicial if not

Euro-centric idea. It is very clear to live in a Yanomamö village, that a guy

who has a lot of close kinsmen, especially brothers, is going to have a lot

more social influence than a guy who has no brothers.

And if your father is polygynous, you are going to have a lot of

brothers. Polygyny is the fount of power. Power and status are almost entirely

a function of how many kinsmen you have, and what kind of kinsmen.

You made a distinction between lowland-villages and villages in more mountainous regions.

The work you are referring to is very recent work that I have done since

1990, when I acquired access to helicopters and airplanes to fly over Yanomamö

territory, and began to realise from an aerial perspective variation in ecology

and geography. I also began using at that time GPS instruments, which enabled

me to precisely locate where every village was. This is probably the most

poorly mapped part of the world.

The villages that I have been studying from the very beginning all are

in the lowland areas. It is not necessarily that these areas are richer, though

you have no tapir or fish in the mountains, it is also easier to make a living

on a flat surface. If you make a garden on a mountain-side with a thirty degree

slope, the amount of effort and calories you have to expend is enormously

greater than making a garden the same size on a flat surface. It is easier to

do all kinds of work: collecting firework, fetching water, chopping down

trees, going hunting. Large gardens are easier to make in the lowlands, but the

lowlands are also easy to traverse and cross if you are going on a raid.

So villages tend to become bigger for defensive purposes in the

lowlands, because it is easier for enemies to reach you on a fairly flat

surface. Since the population is growing, over a time this low-land area gets

filled up with Yanomamö. Well, filled up, the population-density is actually

very low, but villages claim and guard for military reasons a much larger area

than they need for their own immediate subsistence purposes. Because each

village tends to prey on the weaknesses of its neighbours, villages that get

small, get preyed upon, and they have to leave this more desirable area and

move into less desirable terrain, which would be the foothills or the

mountains where living is more difficult. So big villages with larger territories

dominate the lowlands, the losers tend to be get pushed back into the highland

areas, and their villages become smaller.

If this is true, it may explain a lot of the criticism of my work by

some of my colleagues who have studied Yanomamö in other areas. Most of my

critics who are experts on the Yanomamö, have lived in very tiny

Yanomamö-villages, many of which are in the highlands. Once a village gets

smaller, there is less violence, less fighting, less warfare, fewer abductions.

Anthropologists who study these groups are quick to criticize my work where

everything is conducted on a much more intense scale.

Do the Yanomamö understand how western societies are organised?

I once had a fascinating discussion with a Yanomamö, who had a little

bit of training from the missionaries. He had learned some Spanish, and the

missionaries sent him to the territorial capital to acquire some skills in

practical nursing, so he could treat snake-bites and malaria in his own

village. And he told me that when he was in the territorial capital, he discovered

law. He met policemen, and he found out what these people did. They guarantee

the safely of other people in the town, and would protect them from abuse or

violence against them from other people. He was intrigued and fascinated with

that. He thought it was such a marvellous thing, because in his culture his

brothers had killed other Yanomamö, and he was worried that their kinsmen would

seek revenge and kill him, because he would be a legitimate target, the way the

customary system of violence and retribution operates. And he thought it was

just marvellous that law existed, and he thought Yanomamö should have law and

policemen, because it would protect him from possible retaliation for acts that

his brothers committed.

We have our private homes, hide our bodies with clothes, and have other kinds of possibilities for privacy. Is this because we no longer live primarily among kinsmen?

Anthropological textbooks do not always communicate to you the

oppressiveness of having to live among kinsmen. Because they can demand and

compel you to make extraordinary sacrifices, simply because they are your

kinsmen. And it is extremely difficult and tedious to have to live in a

society where you are compelled and obligated to give things to your kinsmen

simply because they are your kinsmen. And you can have lazy kinsmen. You might

want to be a little more ambitious, acquire a few more things and have a

slightly better life than somebody else, but if your brother who is a lazy

lout, comes along and demands half of what your garden produces, you have got

to give it to him. You have no privacy. You are the creature of your relatives.

Probably one of the greatest achievements of western civilisation is to become

independent of that. If you wish, you can be isolated and survive, because

society has institutions that provide you with everything that kinsmen used to

provide people. And you can turn it off and turn it on when you want to.

Functions, like I need legal help, I need protection, and you can shut it off

when it is no longer necessary. But if you live in a kinship-dominated society,

it is always on. The Yanomamö frequently responded to my question: "Why

did you fission into two groups at that site?" by saying something like:

"Because there were too many others and we were sick and tired of fighting

all the time. Everybody was begging everything I had, I got tired of it".

You are pessimistic about the future of the Yanomamö: They are likely to become beggars and bums, alcoholics and prostitutes.

I am making that statement on the basis of my knowledge of what has

happened to other tribal peoples who have been acculturated and missionized in

the lofty and admirable sentiment and objective of making more opportunities

open to them. The opportunities that will be available to the Yanomamö in

Latin America are going to be extraordinarily limited. The best that they can

hope for is getting employment as low-class laborers, or domestic servants in

the households of middle and upper-class people. Which is very common in

Latin-America. "When you go to the jungle, bring me back an Indian",

that is the attitude in Latin America about Indians; they are servants.

They lose their culture, they acquire very expensive appetites for

outboard motors, shotguns and television-sets, but where are they going to get

the money to buy these? They cannot get it at their local village and their

local mission, and the missionaries encourage them to think about moving to

the city. But when they get to the city, nobody is going to hire them. So they

enter the national culture at the lowest economic rung, they get depressed

and dejected and what do they do? They end up as beggars and prostitutes and

bums.

Look at the Indian-reservations of the United States: The highest

alcohol-rates in the world, the highest suicide-rates. And I cannot see this

being any different for the Yanomamö. They have been persuaded in some villages

to give up their own culture on promises of social and material opportunities

that are very unlikely to occur.

But they cannot go on living like they used to.

Why can't they?